1890-1897 The Dream is Born

(From They Dared to Dream, The 18-part History of the IBEW, Thorn Pozen, 1991 & The Electrical Workers' Story)

At the Second Convention of the National Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (as the IBEW was then known), first Grand President Henry Miller said, "No brands of skilled labor ever presented a more unorganized or demoralized condition than that of the Electrical Workers of American in the year of 1889."

But Henry Miller and the other nine men who met in 1891 at the Brotherhood's First Convention had a vision, a dream of workers joining together in strength. From those demoralized and unorganized men has come one of the largest trade unions in North America. Today the IBEW represents almost a million people in all segments of the complex electrical industry. One hundred years later, it can be confidently be said that the dream of the 10 men who met in St. Louis is alive and well.

In 1890, St. Louis was the scene of a national exposition featuring electricity. Electrical workers from around the country traveled to wire the booths, displays and decorations. There, at the end of the day, the men would sit and talk about their working conditions. An hourly wage of 15 cents to 20 cents was considered good, and most made do with $8.00 a week in pay. Apprenticeship training was unheard of, and safety consisted of trial and error and hoping for the best. The men were ready for a change.

A meeting was called at Stolley's Dance Hall, where several members of what was to be called Local 5221 of the American Federation of Labor met with AFL organizer Charles Cassel. Henry Miller, a St. Louis lineman, was elected president and J.T. Kelly, a wireman recently settled in St. Louis, vice president. But these men realized a single isolated local union could accomplish little permanent success without the weight of a national organization of electrical workers behind it. So they set out across the country to organize other locals, hoping to eventually bind them together.

Traveling in railroad boxcars, Henry Miller visited Evansville, Louisville, Indianapolis, Chicago and Milwaukee, organizing as he worked. Unions were organized in Toledo, New Orleans, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Philadelphia and Duluth. Other small organizations of linemen and wiremen in New York, Denver and on the West Coast were contacted.

A year later, in September 1891, the call went out to all those newly organized locals to meet in St. Louis to pull this loose collection of locals into a national union. On November 21, 10 men—T.J. Finnell from Chicago; F.J. Heizleman from Toledo; E.C. Hartung from Indianapolis; Harry Fisher from Evansville; Henry Miller, J.T. Kelly and William Hedden from St. Louis; and J.C. Sutter, Joseph Berlovitz and James Dorsey representing locals by proxy—met at what became the First Convention of the National Brotherhood of Electrical Workers. They met for a week and worked out a constitution and a logo—the now-famous clenched fist holding lightning bolts. Miller was elected first Grand President and Kelly first Grand Secretary.

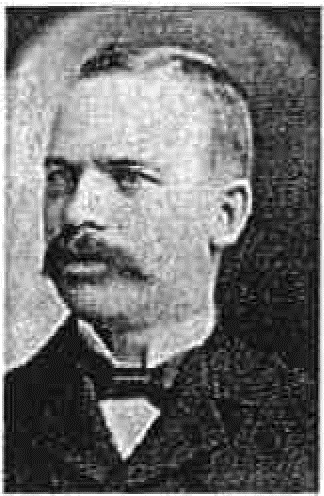

J.T. Kelly wrote of Henry Miller, "Every movement, whether revolutionary or peaceful, every organization established, no matter what the object, has associated with it the name of some individual whose mind conceived and whose energy and perseverance established it; and thus the name of Henry Miller will forever be associated with the organization of the Electrical Workers of America." Henry Miller was born on a ranch near Fredericksburg, Texas, on January 5, 1858. At the age of 14, he worked as a water boy for a government project to string a telegraph line from San Antonio, Texas, to Fort Clark. He became a lineman and made his way around the country working for railroads, Western Union and fledgling electric utilities. By June 1886, he was working for the St. Louis Municipal Electric Light and Power Company. After small attempts at organizing, he saw his chance to begin the process of establishing a citywide and hopefully national, electrical workers' union when electrical workers came to St. Louis for the 1890 exposition featuring electricity.

James T. Kelly was born in Overton, Pennsylvania, in 1862, into a deeply religious family. He started out as a teacher at a small college but gave that up to enter the electrical construction trade as a wireman. He settled in St. Louis around 1890. His only surviving child, John R. Kelly, remembers his father fondly.

Of his father, John wrote, "I remember my father decorating a horse and buggy and participating in several Labor Day parades in St. Louis." He went on to write that his father convinced the city of St. Louis to produce its own power from the steam generated by the boilers in the then new city hospital, an idea still popular today. A powerful speaker and writer, he is credited with writing the preamble to the Brotherhood's first constitution and was the first editor of The Electrical Worker, the predecessor of today's IBEW Journal. J.T. Kelly's wife, Sarah, helped her husband a great deal throughout his organizing efforts.

After the First Convention adjourned, President Miller traveled to Birmingham, Alabama, where the AFL was holding its annual convention. On December 4, 1891, the Brotherhood received a charter from the AFL with jurisdiction over all electrical work. In a letter written to J.T. Kelly dated December 5, 1891, Samuel Gompers, AFL president, said, "I am more pleased than it is possible for me to give expression to you that your National organization has been brought into existence."

Brother Miller continued traveling and organized locals all up the East Coast. T.J. Finnell of Chicago, elected Grand Organizer at the First Convention, concentrated his organizing efforts on the Midwest. A year after its founding the Brotherhood boasted 45 locals.

The second national convention of the Brotherhood was held in Chicago in November 1892 amid great optimism. With 26 delegates representing approximately 2,000 members from around the country, Henry Miller had reason to feel secure. He said, "From present indications the continued growth of the Brotherhood, both in local unions and in large membership, is well-assured." Both Kelly and Miller were reelected; The Electrical Worker was founded; the death-benefit payments, which went out to members and their spouses, were doubled; and the future looked promising.

The optimism of 1892, however, soon gave way to the "Panic of 1893." The national economy went into a tailspin; investment in electrical plants, which had seen tremendous growth in the past five years, dried up; companies folded—even the recently founded giant, General Electric, barely avoided bankruptcy. The Electrical Worker noted in August 1893 that the national electric trade was at a standstill and that it was "going to be a very hard winter."

Between July and November 1893, the Brotherhood lost around 600 members; and the attitude of those who remained was rapidly deteriorating. There was feuding among locals over jurisdiction in the New York and Chicago areas. There were also problems with unauthorized strikes.

By the Third Convention, held in Cleveland in November 1893, the Brotherhood was in trouble. The union was in debt, morale was low and tensions were high. Brother Q. Jansen, a lineman from Local 2, Milwaukee, was elected Grand President; and Henry Miller became Third Grand Vice President and Grand Organizer. J.T. Kelly was re-elected Grand Secretary. The delegates voted to raise the per capita tax and assessment for The Electrical Worker and to hold the Convention every two years in an effort to regain financial stability.

Only 11 delegates attended the Fourth Convention in 1895 in Washington, D.C. Times were hard. Secretary Kelly went as far as to mortgage his house and personal possessions to ensure the Brotherhood's operating funds. But things were turning around. Belt tightening by the union and a general economic upturn gave the Brotherhood a positive balance in the treasury by the Fifth Convention held in Detroit in 1897. New locals were signed on, and strikes were held to a minimum.

The Convention of 1897 paid special tribute to Brother Kelly, who stepped down as Grand Secretary after bringing the union through one of its hardest times. The delegates adopted a resolution thanking him for his "unsullied and valuable services," and he returned to St. Louis where he remained until his death a vocal and active member of Local 1. The Convention delegates also formally praised their former Grand President, Henry Miller. Like so many of the early linemen, Henry Miller died young—July 10, 1896, in Washington, D.C., after sustaining a severe electric shock and falling from a utility pole. He was 38 years old. In 1897 the delegates voted to have his grave appropriately decorated.

J.T. Kelly wrote of Henry Miller, "He was generous, unselfish and devoted himself to the task of organizing the electrical workers with an energy that brooked no failure. . . ." That devotion to the task of organizing, that capacity to turn plans into action, to change a dream of unity and bargaining power into the reality of the Brotherhood, the delegates observed, indebts all union members to the legacy of Henry Miller. And through J.T. Kelly's extraordinary efforts, that legacy lives on today.

Excerpt by Carl D. Cantrell, 10th District